- Home

- Melody Carlson

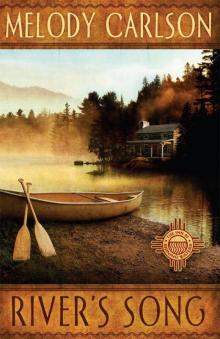

River's Song - The Inn at Shining Waters Series Page 5

River's Song - The Inn at Shining Waters Series Read online

Page 5

"Your mama loved your letters. She saved every one, you know—reading them again and again. She said they were like medicine. Good medicine."

"It wasn't that I saw the world through rose-colored glasses, but it didn't hurt to hope for better days. My letters became so convincing that I almost believed them myself by the time I sealed up the envelopes and stuck on the stamps. And there seemed no reason to think my parents ever suspected anything different. Then, after Daddy developed his heart condition, it had seemed best to keep up my charade. No need to add stress to his life."

"But after he died?" Babette tipped her head to one side." Why not tell your mama the truth then?"

"Mother was so overwhelmed with grief, she needed me to be strong for her."

"Then why not stay here then? You and Lauren could've lived right here—very happily."

"I still had Adam to care for. His mother had made it clear from the moment he came home from the war that he was my responsibility. And Lauren had school and her friends and activities by then. I thought she'd enjoy seeing where I grew up, but she seemed to hate it. She'd already been influenced by her other grandmother. She wasn't quite eleven and she was already turning up her nose like a spoiled teenager. She thought everyone here was backward and she called the Siuslaw a backwater. Thankfully, my mother never heard her say these things, but I know Lauren is ashamed of her Indian heritage. She is ashamed of me."

"Oh, Anna." Babette had tears in her eyes now. "I am so sorry, chérie." She got up and gathered Anna in her arms, squeezing her tightly, smelling of sweet French perfume. "So very sorry." Babette went over for the coffee pot, refilled their coffee cups, and sat down again. Retrieving a lace-trimmed handkerchief from the bodice of her dress, she daubed her eyes.

"And now I've made you sad." Anna stirred a bit of sugar in her coffee.

"Because I love you, I am sad. Now, please, tell me the rest of your story."

"There's really not much else to tell. I took care of Adam and Lauren and did all the housekeeping in Eunice's house—"

"You kept house for that wicked woman?"

"I had no choice. She and the doctor insisted that Adam needed to live in her house to receive adequate care. He was taken immediately to his old bedroom." She shook her head." And that's where he remained for the next seven years . . . until he passed." Anna didn't have the strength to say that Adam took his own life. No one had ever spoken those words before, but Anna knew in her heart it was true. She suspected Adam had saved up several weeks' worth of pain pills, the ones she carefully doled out daily. His lack of medication would explain his horrid meanness in the last weeks of his life. And, really, on so very many levels, she didn't blame him for doing it. It would be up to God to sort that one out.

"But why did you not come home then?"

Anna sighed. "Lauren."

"Oh. . . ." She nodded sadly. "I see."

"How could I drag her away from everything she loved? And even though I could see my mother-in-law turning my daughter into a brat, how could I abandon my own daughter? I suppose I hoped that I would still be able to influence her . . .that she would grow up and see that Grandma Eunice has her faults. But I'm afraid all Lauren sees is that Grandma Eunice has a fat pocketbook. And I have nothing. And so I kept my troubles bottled up inside and continued writing my sunny letters to mother. And now she is gone." Suddenly Anna was crying again. As if all that she had lost came rushing at her like a tidal wave. "Oh, Babette!" she cried. "She is gone. Truly gone!"

Now they both cried. Flooded with regret, Anna wished with all her heart that she'd come back to her mother sooner— before it was too late. Why hadn't she simply packed up Lauren and brought her back here? Eventually, Lauren would've gotten used to the slower-paced life. She would've made friends. Perhaps she would've grown to love the river eventually. And now she never would.

"I wish I'd been honest. I wish I'd told Mother all about my life,"Anna said through her tears. "All about Adam's problems, how it felt having my mean mother-in-law breathing down my neck all the time, putting me down, calling me names. I wish I'd confessed to Mother that I was letting my daughter push me around—the same way I allowed Eunice to bully me. I should've told her everything."

"Maybe not, chérie."

Anna blinked, blotting her eyes with her own handkerchief now. "Why not?"

"I think it would have crushed her."

"Your mama she was a wise woman in her way."

"Oh."

"Yes." Anna nodded.

"She knew things about Adam . . . things she never told anyone except me."

"What?"Anna waited anxiously.

"Your mama saw a weakness in him. She hoped it was only youth. But when you called her to say you were married—so quickly—your mama, she was worried."

"I know . . . I could hear it in her voice."

"Her worry . . . it make her sick . . . such stomach troubles." Babette shook her head. "All from too much worrying."

"Poor Mother."

"So your letters come . . . and the sun it comes out . . . your mama, she happy. Her stomach is well. Like I said, your letters were good medicine."

Anna thought about this. Perhaps her pretense at a happy life had prolonged her mother's life. Maybe it had all been for the best. At least for her mother. "Do you think she knows the truth now, Babette? That all wasn't as it seemed in my life?"

"I do not know about that, chérie. But I do believe she is in heaven and to be in heaven is to be happy, so I think this—if your mama knows your story, the sad story you have just told me, then she also knows the other part of your story."

"The other part?"

"The part that is not yet to happen!" Babette laughed. "And I am sure it will be the happy part."

Anna sighed. "I hope you're right. You know, if Mother was here right now, I would tell her everything. I would admit that her concerns about marrying so quickly were justified. I would confess that the weakness she saw in Adam was correct, and that I was blinded to it at the time. It was just like that song Lauren listens to on her record player."

"What's that?"

"The words go something like this: when you're heart's on fire, smoke gets in your eyes." She shook her head. "But what the song fails to mention is that sometimes when your heart's on fire you get badly burned."

Babette laughed. "Oh, I could tell you that, chérie."

"But Mother never told me much about love and romance while I was growing up. I watched it in the motion pictures at the Saturday matinees, but the silver screen was always filled with heat and passion and fire."

"Oh, Hollywood, they are expert at making it sizzle.""But for the most part the characters didn't get burned in the movies, not in the ending anyway." At least that was true in the movies she'd liked. "I remember they got singed from time to time, but in the end they usually wound up with their true love, presumably living happily ever after."

"Except for Casablanca," Babette reminded her. "And Gone with the Wind."

"That's true. Perhaps I should've paid closer attention to those films. Maybe I would've learned something useful."

"You had your parents' marriage," Babette pointed out." They were happy."

"Yes, they had a few squabbles, but for the most part they made it look fairly easy. Nothing like what I experienced in my life."

"Just remember this, chérie." Babette stood. "Your life is not over."

Anna gave her a weary smile. "It feels like it is."

"It is only beginning, chérie. Trust Babette." Now she touched Anna's cheek. "But you do not want to look like it is over. You must take care!"And now she promised to bring by a special facial cream on her next visit. "Before it is too late for your pretty face."

Anna walked her back down to the dock, untying her rope and handing it to her. "Thank you for coming by," she said." And remember what you said about how my letters were good medicine for my mother?"

"Oh, yes." Babette put on her broad-brimmed straw river hat, tying the

ribbons beneath her chin. "Very good medicine."

Babette grinned. "There ees lots more where that comes from!" She leaned over and reached for the cord to the motor, pulling it out with surprising strength. Impressive for her age, which Anna guessed must be more than sixty now, although she wasn't sure. The engine roared to life and Babette waved." Adieu!"

"That's what you were for me today. Good medicine. Thanks!"

"Adieu!"Anna called back, watching as the small boat sliced a path through the glass-like surface of the river.

Suddenly, Anna had an idea. She would take out the River Dove. Hopefully it would still be seaworthy, or at least riverworthy. Hopefully she would be as well.

6

Anna felt slightly silly as she went to get her canoe. Not for wanting to take a boat ride. There was nothing silly about that. But she felt slightly silly because she'd taken her long hair out of its customary "old lady bun"As Lauren liked to call it, and divided it into two long braids. This was something she would never dare do back in Pine Ridge. Between Eunice and Lauren, the teasing would be unbearable. However, here on the river, it felt perfect. And because she'd brought no casual clothes, she went through her parents' closet to discover some of her dad's old work clothes. Finding a pair of corduroy pants and a tan work shirt, she outfitted herself for a nice little row on the river. And if she fell in, which she hoped would not happen, she would not be the worse for wear. However, she knew that if someone like Eunice or Lauren spotted her looking like this, they would probably laugh.

"Well, let them laugh," she said with determined resolve as she tugged the canoe out from where it had been stored back behind Grandma Pearl's old cabin. She'd brought rags to wipe out the canoe with and, naturally, it was full of spiderwebs and such. But before long, it looked as good as new—or as good as when it had been given to her. The oar was in good shape too. Obviously, someone had made this canoe to last.

She slipped the small vessel into the water next to the dock, then carefully—very carefully—she stepped one foot into the center of the boat and, holding both sides with both hands, she slipped the other in as well. The canoe tipped back and forth a bit but she resisted the urge to leap out; instead she took in a slow, deep breath and, still holding to the sides, she held her torso erect and slowly squatted to a sitting position. She released the breath and smiled at her accomplishment. Now, picking up the oar, she used it to give herself a gentle shove from the dock, which rocked the canoe even more, but once again she took in a deep breath and resisted the urge to overcorrect. Instead, she waited, slowly releasing her breath, and just like that the canoe stopped rocking. Holding itself evenly in the water, the canoe now glided out onto the river, almost as if it knew exactly what it was doing. Maybe it did.

Canoeing came back to her—perhaps in the way people said riding a bike would do, except that Anna had never learned to ride a bike. There was no place on the river to ride to. Boats were the way to travel. Although she'd heard there was a gravel road running out behind the property now, and that it supposedly connected to town, it would take two to three times as long to drive as to go down the river. And most folks thought it was a waste of taxpayers' money.

Anna felt like someone else as she peacefully paddled along—or maybe she was finally just her old self again—but it felt amazingly good . . . and right . . . and true. Even so, she finally got to the place where she knew she should turn back. Really, what was she doing here? Out paddling around the river like she was twelve. And here she had a daughter back home, probably wondering when her mother was coming back. And Eunice was probably piling up the household chores, making a new to-do list, just waiting for her "squaw" to get back to put the place in order again. "It's how she earns her keep," Eunice would tell anyone who was bold enough to inquire about the curious arrangement between the two women.

Anna had no doubts that Eunice shelled out a fair amount of money on account of them. At least on account of Lauren, since Anna lived simply enough. But between her daughter's expensive taste in clothes and her appetite for social activities, not to mention the convertible Eunice had gotten Lauren for graduation, well, there was no way Anna could afford such luxuries. Working for Eunice was her contribution.

"You do realize that you're entitled to some of your husband's assets," the family attorney, Joseph P. Miller, had told her once when she'd run into him at the hardware store not long after Adam had passed. "Why don't you come into my office sometime?"

Of course, when Anna had set out a week or so later, planning to walk into town to pay Mr. Miller a visit, Eunice had stopped her even before she got out the door. "Where are you going all dressed up today?"

"To town."

"What for?"

"To attend to some business." Anna reached for the doorknob, wishing she'd timed her getaway a little better, or perhaps hadn't bothered to wear her good gray suit, one she had sewn for herself and felt looked nearly as good as the ones Eunice spent far too much money on.

"What sort of business?"

Anna had looked directly at her mother-in-law then. Really, it seemed pointless to attempt to keep anything from her. She would find out eventually. Nothing Anna did in this town, and it wasn't much, ever escaped Eunice Gunderson's notice. So Anna told her the truth.

"Well, that's ridiculous." Eunice waved her hand. "Adam's assets ran out ages ago. In fact, if I wanted, I could probably charge you for all the assistance I've given to Lauren and you all these years. But, of course, we're family. I would never dream of doing that. But if you feel you must go see Joe, I'm happy to drive you there myself. Did you make an appointment?"

"No, I, uh . . . well, I just thought I'd drop in."

Eunice laughed. "Drop in? Don't you know he's a very busy attorney? He handles all of the mill's business and I happen to know that this week he has quite a bit on his plate. In the future, I suggest you make an appointment if you care to see him. And keep in mind his hourly rate." She made a tsk-tsk sound. "And it just went up too. Scandalous what lawyers imagine they are worth these days."

Naturally, Anna didn't go see Joseph Miller that day or any other day. She had long since accepted that the only two things Adam left to her were a wedding ring, which she had safely tucked away, and Lauren. She looked at the canoe beneath her, realizing it was probably worth more to her than her wedding ring and, although she didn't love it more than her daughter, it had probably given her more pleasure. Sad—but true.

"Hello over there!"

Anna looked up in surprise. She hadn't heard any other boat motors, but now saw that this was a rowboat, with a grayhaired woman waving from it. "Hello,"Anna called back. She didn't recognize the woman, but then it had been years and people, including her, could change.

"Do you live around here?" the woman called as she clumsily rowed over with an eager smile.

"Sort of. Anyway, I used to."

The woman got closer and peered curiously at her. "I couldn't help but notice your dugout canoe. It seems authentic. Are you a native?"

"Native?"Anna frowned as she recalled an old Laurel and Hardy movie about African headhunters. Hadn't they called them natives?

"I mean a Native American? An American Indian? Are you?" The woman looked excited now, as if she'd just made an unusual discovery and might suddenly whip out a camera to document it by snapping a photo of Anna. Or perhaps she planned to trap Anna and carry her back to a Ripley's museum as an exhibit—they might title her cage "the last of her breed."

Anna knew she was being slightly ridiculous, but just the same she did not answer this strange woman.

"I'm sorry." The woman looked deflated now. "In my enthusiasm, I've made it sound all wrong. It's just that I'm so happy to see you today."

Anna remained silent, studying the woman, trying to figure her out. Dressed for the outdoors, almost as if she was going on some kind of safari expedition, she looked fairly normal, although her words sounded a bit nutty.

"You see, I'm an anthropologist. I'm doing my

doctoral thesis on coastal Indian tribes and their customs. And, well, they are just so hard to find these days. And I saw you in your beautiful canoe and you looked like you could possibly be a descendant of an American Indian tribe. Please, I beg you, excuse my bad manners. Just attribute it to my age and my passion for Indian history. I am sorry to have offended you."

"Well, at least you didn't say 'How.' "

The woman laughed. "Thank goodness for that. Let me start over. My name is Hazel Chenowith. I'm from the University of Oregon and I'm spending my summer on the Oregon coast, doing research and writing. Today I'm exploring on the river."

"I'm Anna Gunderson," she said politely. "My parents owned what used to be a small general store over on the river. I'm staying there for a few days."

"Oh, yes. Someone told me about that the other day. A man from town gave me a tour of the river in his speedboat, but he went too fast. However, I did see the place, the gray square building with a faded General Store sign?" Hazel maneuvered her rowboat adjacent to Anna's canoe now, close enough for the women to shake hands if they wanted to. Not that Anna wanted to.

"That sounds right."

"And your mother descended from the Siuslaw Tribe, correct?"

"Yes."

"I'm sorry . . . I just heard of her passing the other day. The man in the speedboat mentioned it. Please accept my sincerest sympathies."

"Thank you."

"I was so disappointed to hear of her death. I know it sounds terribly self-serving, but I had sincerely hoped to meet her and speak with her about her heritage."

Anna shrugged. "Well, you shouldn't feel too bad. I doubt my mother would've told you much."

"Why is that?" Hazel removed her wire-rimmed glasses and, pulling out a man's handkerchief, paused to wipe them clean. "That is, if you don't mind me asking."

"My mother was one hundred percent Indian, but she lived out her life as a white woman. Other than her skin, which she guarded religiously from the sun, you would not have known about her heritage."

The Happy Camper

The Happy Camper Courting Mr. Emerson

Courting Mr. Emerson The Christmas Swap

The Christmas Swap Lost in Las Vegas

Lost in Las Vegas The Christmas Shoppe

The Christmas Shoppe Becoming Me

Becoming Me Finding Alice

Finding Alice Payback

Payback All for One

All for One Under a Summer Sky--A Savannah Romance

Under a Summer Sky--A Savannah Romance Face the Music

Face the Music Catwalk

Catwalk Never Been Kissed

Never Been Kissed Allison O'Brian on Her Own

Allison O'Brian on Her Own An Irish Christmas

An Irish Christmas Beyond Reach

Beyond Reach Faded Denim: Color Me Trapped

Faded Denim: Color Me Trapped Three Weddings and a Bar Mitzvah

Three Weddings and a Bar Mitzvah Here's to Friends

Here's to Friends On My Own

On My Own River's Call

River's Call New York Debut

New York Debut Homeward

Homeward Love Finds You in Sisters, Oregon

Love Finds You in Sisters, Oregon Viva Vermont!

Viva Vermont! Notes from a Spinning Planet—Ireland

Notes from a Spinning Planet—Ireland Harsh Pink with Bonus Content

Harsh Pink with Bonus Content Perfect Alibi

Perfect Alibi The Christmas Pony

The Christmas Pony All Summer Long

All Summer Long These Boots Weren't Made for Walking

These Boots Weren't Made for Walking Back Home Again

Back Home Again Torch Red: Color Me Torn with Bonus Content

Torch Red: Color Me Torn with Bonus Content Bitter Rose

Bitter Rose Spring Broke

Spring Broke Sold Out

Sold Out LimeLight

LimeLight Double Date

Double Date Homecoming Queen

Homecoming Queen A Not-So-Simple Life

A Not-So-Simple Life My Name Is Chloe

My Name Is Chloe My Amish Boyfriend

My Amish Boyfriend Once Upon a Summertime

Once Upon a Summertime Let Them Eat Fruitcake

Let Them Eat Fruitcake Deep Green: Color Me Jealous with Bonus Content

Deep Green: Color Me Jealous with Bonus Content The Joy of Christmas

The Joy of Christmas Memories from Acorn Hill

Memories from Acorn Hill Premiere

Premiere A Mile in My Flip-Flops

A Mile in My Flip-Flops As Young As We Feel

As Young As We Feel Deceived: Lured from the Truth (Secrets)

Deceived: Lured from the Truth (Secrets) Take Charge

Take Charge Road Trip

Road Trip A Simple Song

A Simple Song Three Days: A Mother's Story

Three Days: A Mother's Story A Dream for Tomorrow

A Dream for Tomorrow Looking for Cassandra Jane (The Second Chances Novels)

Looking for Cassandra Jane (The Second Chances Novels) Against the Tide

Against the Tide Your Heart's Desire

Your Heart's Desire The Christmas Blessing

The Christmas Blessing Love Gently Falling

Love Gently Falling On This Day

On This Day The Christmas Joy Ride

The Christmas Joy Ride Ciao

Ciao The Christmas Bus

The Christmas Bus Blade Silver: Color Me Scarred

Blade Silver: Color Me Scarred Dating Games #1

Dating Games #1 Double Take

Double Take Falling Up

Falling Up Last Dance

Last Dance Westward Hearts

Westward Hearts Glamour

Glamour Crystal Lies

Crystal Lies The Best Friend

The Best Friend Prom Date

Prom Date The Christmas Angel Project

The Christmas Angel Project Raising Faith

Raising Faith The 'Naturals: Awakening (Episodes 1-4 -- Season 1) (The 'Naturals: Awakening Season One Boxset)

The 'Naturals: Awakening (Episodes 1-4 -- Season 1) (The 'Naturals: Awakening Season One Boxset) Allison O'Brian on Her Own, Volume 2

Allison O'Brian on Her Own, Volume 2 Notes from a Spinning Planet—Papua New Guinea

Notes from a Spinning Planet—Papua New Guinea Once Upon a Winter's Heart

Once Upon a Winter's Heart Damaged

Damaged Lock, Stock, and Over a Barrel

Lock, Stock, and Over a Barrel Hometown Ties

Hometown Ties Anything but Normal

Anything but Normal Jerk Magnet, The (Life at Kingston High Book #1)

Jerk Magnet, The (Life at Kingston High Book #1) Damaged: A Violated Trust (Secrets)

Damaged: A Violated Trust (Secrets) Fool's Gold

Fool's Gold Girl Power

Girl Power Forgotten: Seventeen and Homeless

Forgotten: Seventeen and Homeless Trading Secrets

Trading Secrets Blood Sisters

Blood Sisters Bad Connection

Bad Connection Spotlight

Spotlight A Simple Christmas Wish

A Simple Christmas Wish Love Finds You in Martha's Vineyard

Love Finds You in Martha's Vineyard Angels in the Snow

Angels in the Snow A Christmas by the Sea

A Christmas by the Sea It's My Life

It's My Life Mixed Bags

Mixed Bags The Christmas Dog

The Christmas Dog Secret Admirer

Secret Admirer Love Finds You in Pendleton, Oregon

Love Finds You in Pendleton, Oregon Trapped: Caught in a Lie (Secrets)

Trapped: Caught in a Lie (Secrets) The Gift of Christmas Present

The Gift of Christmas Present Hidden History

Hidden History Meant to Be

Meant to Be The Treasure of Christmas

The Treasure of Christmas Just Another Girl

Just Another Girl River's Song - The Inn at Shining Waters Series

River's Song - The Inn at Shining Waters Series That Was Then...

That Was Then... Burnt Orange

Burnt Orange Spring Breakdown

Spring Breakdown The Christmas Cat

The Christmas Cat Christmas at Harrington's

Christmas at Harrington's